Will Art Save Us?

Using artistic expression to process pandemic life

by Lauren Macknight

"You hope you never have to use this knowledge, but you're incredibly grateful that you have it when you do." — UT Associate Professor of Art Education Donalyn Heise

On Sept. 24, Austin hit the six-month mark since the day our world seemingly tilted on its axis. However, it wasn't as if the entire nation shuttered within one day in unison back in March. It felt disjointed and still does. For those in Los Angeles, that six-month mark came around Sept. 19; for Seattle, Sept. 23; and for New York, Sept. 22 marked six months since Gov. Andrew Cuomo issued public health orders to stay home.

We may all be experiencing the ramifications of the novel coronavirus pandemic, but we are each experiencing it differently. Beyond individual cities and public health orders, the pandemic's consequences have been felt as both a global and profoundly solitary event. For researchers who study trauma, the combined and ongoing effects of stress related to fear of potential infection, financial stress due to economic precarity and the stress of social isolation and the disruption to school and routines have signaled an increasing likelihood of traumatic stress at scale. So how do we respond—as individuals, as communities, as artists and as educators?

As a University of Texas at Austin Art Education associate professor, Donalyn Heise strives to meet her students' needs while also anticipating the needs of future students through her curriculum. Drawing upon more than 30 years of experience in K-12 public and private arts education and work in at-risk communities, Heise’s research encompasses multiple disciplines including art therapy, social work, psychology and general education. This month, she will present her arts education work on using art for fostering resilience at the Partners in Prevention Virtual Conference, a conference on youth and child development for educators, youth service providers, civic leaders, policy advocates and researchers. At UT Austin, Heise imparts a wealth of knowledge and research that informs her approach to arts education and fostering resilience in diverse populations. A cornerstone of that approach is an understanding of trauma, its many forms and effects.

When most people imagine trauma, they associate it with violence. Post-traumatic stress (PTS) is defined by the experience of a traumatic event, such as a war or sexual assault. However, the term trauma actually covers a wide range of experiences and events that can have a crippling effect on social and mental well-being. The experience of the pandemic and its social and economic consequences have exacted an emotional toll over time. "A stressor can become traumatic when it overwhelms a person's ability to cope psychologically and physically," wrote Bessel van der Kolk, a Boston University School of Medicine psychiatry professor and trauma researcher who has studied post-traumatic stress since the 1970s. "Traumatized people chronically feel unsafe inside their bodies: The past is alive in the form of gnawing interior discomfort." Van der Kolk's research is often cited by art therapists and arts educators including Heise and her colleagues using a trauma-informed approach.

Art education researchers such as Heise ask the question: What makes some people cope while others crumble in the face of adversity? Heise has studied the effects of trauma on school-aged children and used resilience theory as a jumping-off point for employing the visual arts as a tool for communication, self-reflection and healing.

Resilience theory emerged in opposition to another prevention-based model that emphasized risks and deficits. By comparison, resilience theory recognizes strengths, assets and protective factors. Heise’s work shows how the arts can help foster resilience in students by building resourcefulness, personal accomplishment, creativity, persistence, a vision of the future, a dedication to contributing to the well-being and betterment of others and awareness of one’s own thought processes. By developing arts lessons that build upon these protective factors, arts educators can unlock the visual arts' creative and healing potential.

Heise brought this research into practice in her classroom at UT last spring, when she encouraged her Art Education students to keep a journal of "visual notes," a method of chronicling experience that allows for self-examination and growth. Erin Frisch, a master's candidate in Art Education, took the assignment a step further:

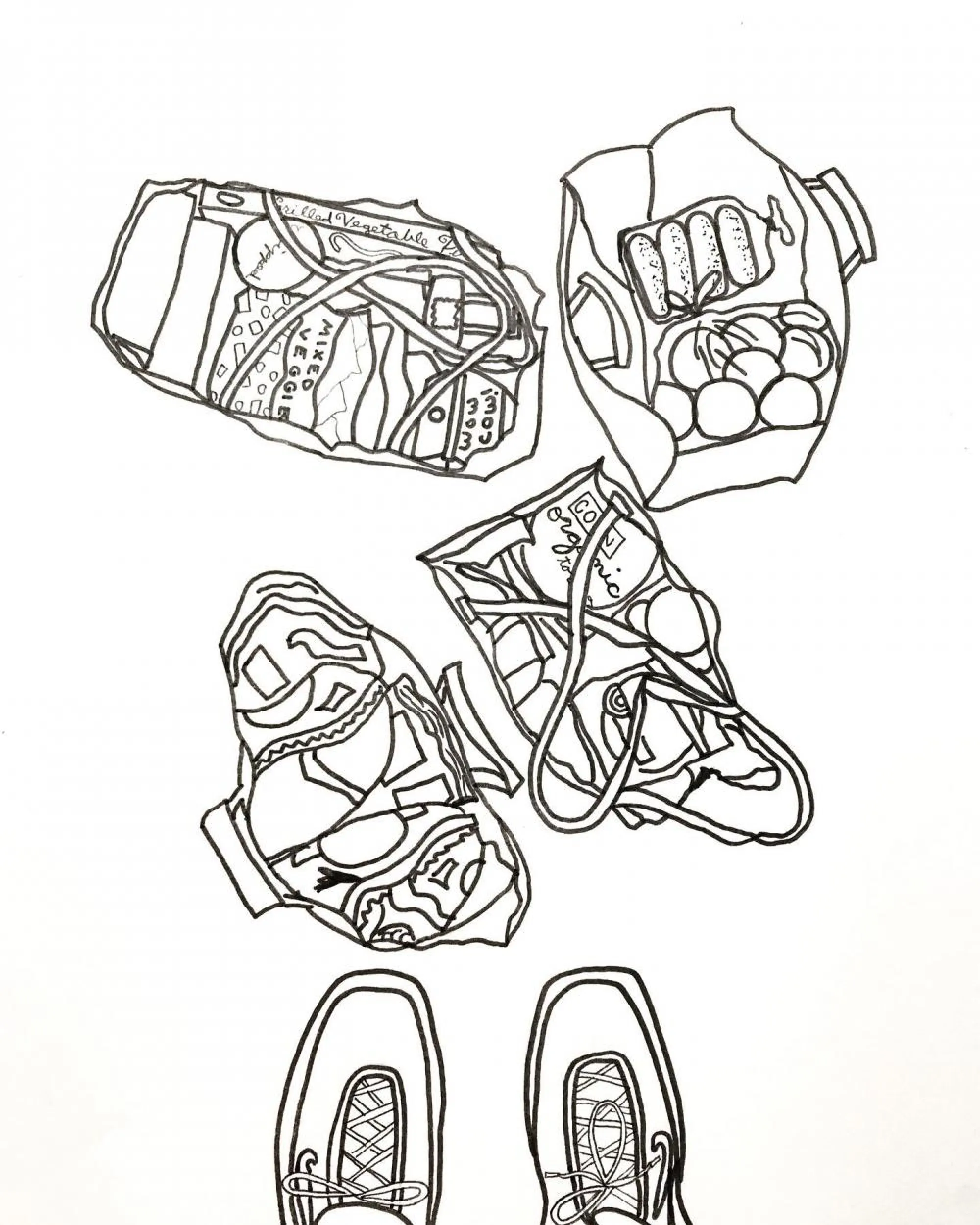

In March, I started documenting moments of my life at home during lockdown through drawing in a “social distancing diary” that I shared on Instagram. After bringing home a huge grocery shop to avoid going to the store frequently, I was struck by the uncanny feeling of how unusual my life had become. I worried about food scarcity and the homeless. So, I drew my grocery bags and shared my feelings online. Working through my emotions using art was important, but I also wanted to share these thoughts online in case others felt the same.

…During lockdown, artmaking served as a critical source of respite and joy that we could find at home. I hope that the people who have discovered artmaking during the pandemic can continue to use it as a tool for reflection and self-care.

Processing emotion and making visible intangible thoughts, feelings and concepts is at the heart of art making and the creative process. Studio assignments ask students to step away from normal routine and play with materials, images and ideas. It’s a liberating process that allows access to unprocessed feelings and an alternative path toward connection with others through their work.

As part of an assignment for her Advanced Drawing course back in April, Studio Art faculty member Megan Hildebrandt asked her students to consider the window as, among other things, a site of connection. Students created drawings, animations and video in response. When Studio Art major JJ Barrett started to work on the project, he found himself pushing at its bounds and distinctly reacting to how he was experiencing life during the pandemic.

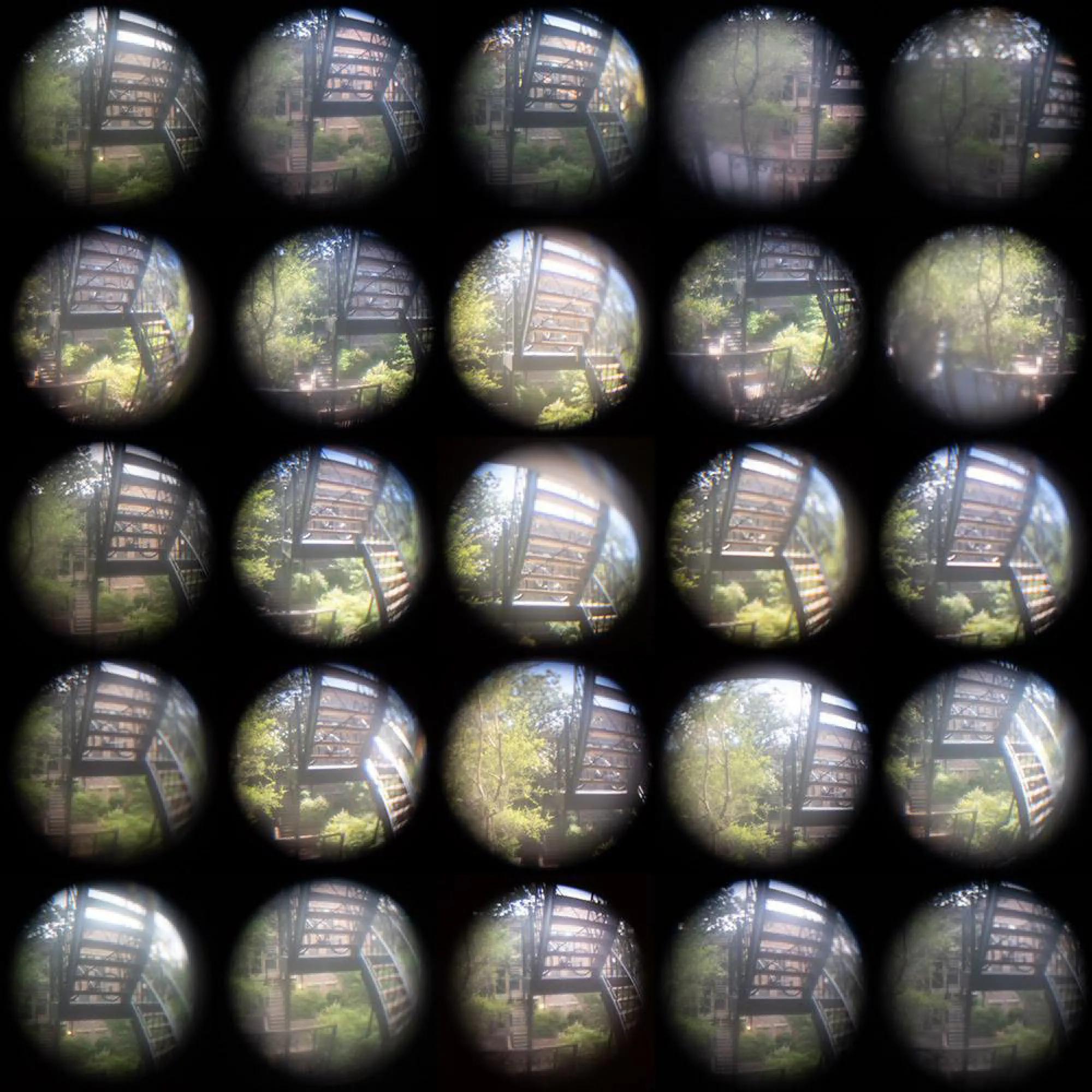

Barrett describes himself as someone who is at ease with his independence and being alone. He felt comfortable, maybe even prepared to face the requirements of lockdown. But something shifted during that first month between mid-March to mid-April, and he felt it in his sleep schedule. Without the structure of going to classes and social engagements, his schedule became somewhat shapeless, defined by the feeling of time passing instead of the typical markers of a passing day. When he was tackling the prompt of the assignment, Barrett's life seeped in. The images in his final work, Peephole, are based on a set of conditions: During a five-day period, he would go to his front door and look through the peephole five times a day to take five separate images. Inspired by artist Steven Pippin's Laundromat-Locomotion series—a series that was inspired by photographer Eadweard Muybridge's photographs of motion—Barrett seemed to try to solve the riddle of how to depict a kind of restless immobility of self-imposed isolation. The practice of taking the photos gave structure to his day, and that satisfying structure is reflected in the comforting symmetry of the work's shapes and neat grid. Barrett was imposing a kind of order on chaos, a meaning-making that Heise might identify as an arts-based protective factor.

Another of Hildebrandt's students, Studio Art major Mia Batts, creates work that is often steeped in emotion, guided by narrative and imagination. Under stay-at-home orders, Batts experienced the feeling of being flooded with ideas and thoughts, but she lacked the ability to edit and execute them. "Being productive prevents [feelings of being overwhelmed], but all that time with nothing to do; I had no choice but to confront my emotions," says Batts about a turning point when she accepted that she could no longer ignore her stress and anxiety. "Shutting away my thoughts meant shutting away my imagination."

Batts started depicting glimpses of her days in isolation, using washes of blue, black and rusty red inks and gestural pen strokes to infuse her work with emotional weight. These pieces feel like vignettes brought together in a layout similar to a graphic novel in subdivided frames. In one frame, the perspective shows the artist's figure fully clothed in a bathtub from above as she rests her hand on her forehead. "I have my own bathroom so…" is handwritten beneath the frame, trailing off with unanswered questions about what a single bathroom affords. Much like Heise's visual notes exercise, Batts' drawings are both an exercise in self-examination, understanding and an attempt at connection. Batts hopes to one day bring these drawings and paintings together into an artist monograph.

"I have never thought so much about the state of the world and what the future will bring until now," says Batts. "I come across news segments, video clips and articles related to [current social and economic events] numerous times. I receive concerning news from loved ones at home. It is hard to ignore it all unless I stay away from the media altogether, but the ability to share my art is what keeps me connected to others."

For Batts and other student artists, their work offers one of the few avenues toward connection and community during a moment when it is unsafe to gather. As we face the possibility of yet more months of possible lockdown and restrictions and sustained urgency to meet the demands of social justice, it's important to safeguard against the weathering effects of isolation and prolonged stress. "A trauma-informed curricular framework cultivates self-esteem, meaning-making and healthy relationships with others in the context of art-making," writes art educator and art therapist Lisa Kay in her most recent book, Therapeutic Approaches in Art Education. Trauma-informed art educators such as Kay and Heise know that we can employ the arts to mitigate the effects of isolation through connection with others and communicating our experiences through images when we don't have words.