Reviving Erased History

How Associate Professor Kate Catterall used design to resurface a Belfast memory buried for 25 years

by Cami Yates

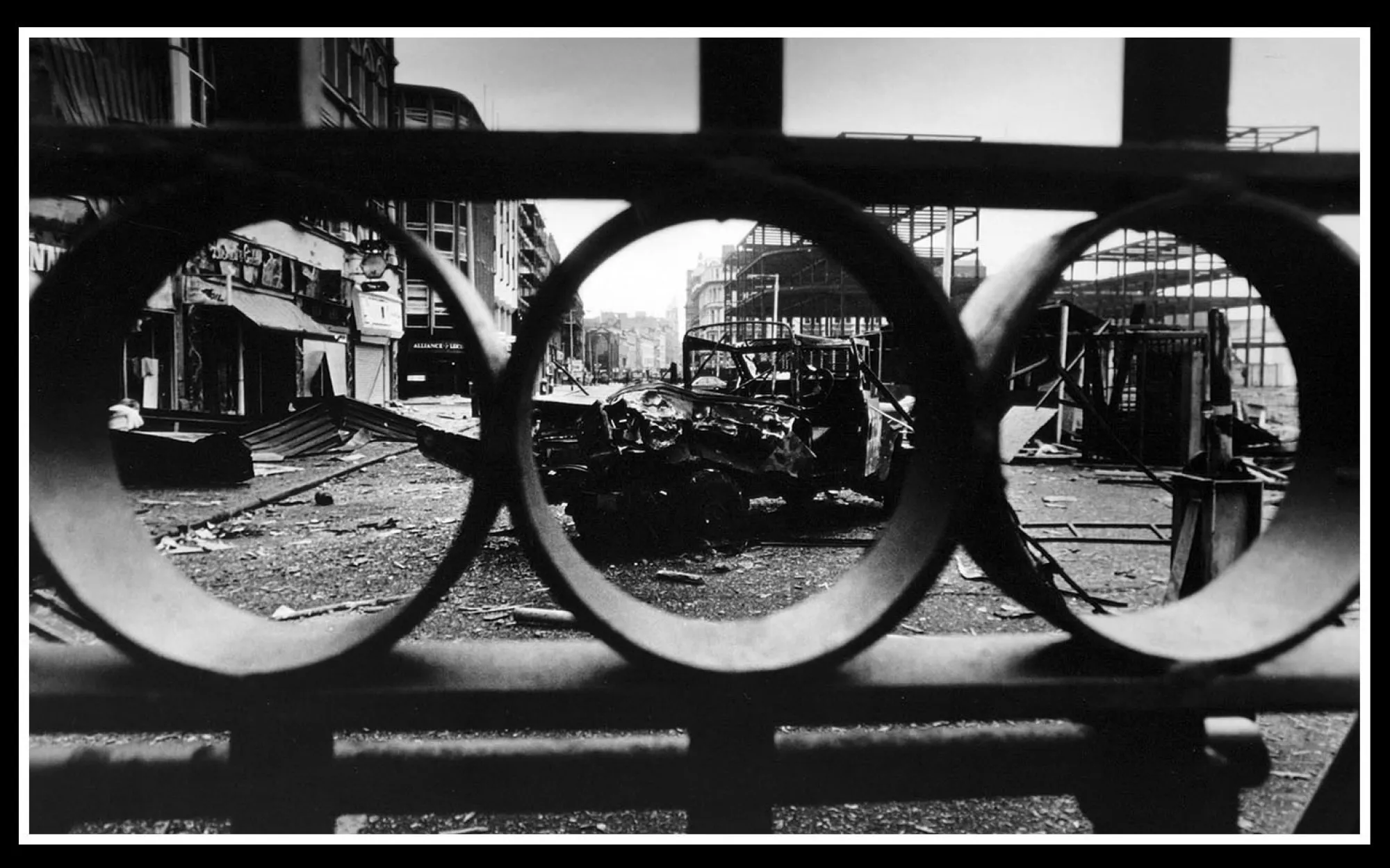

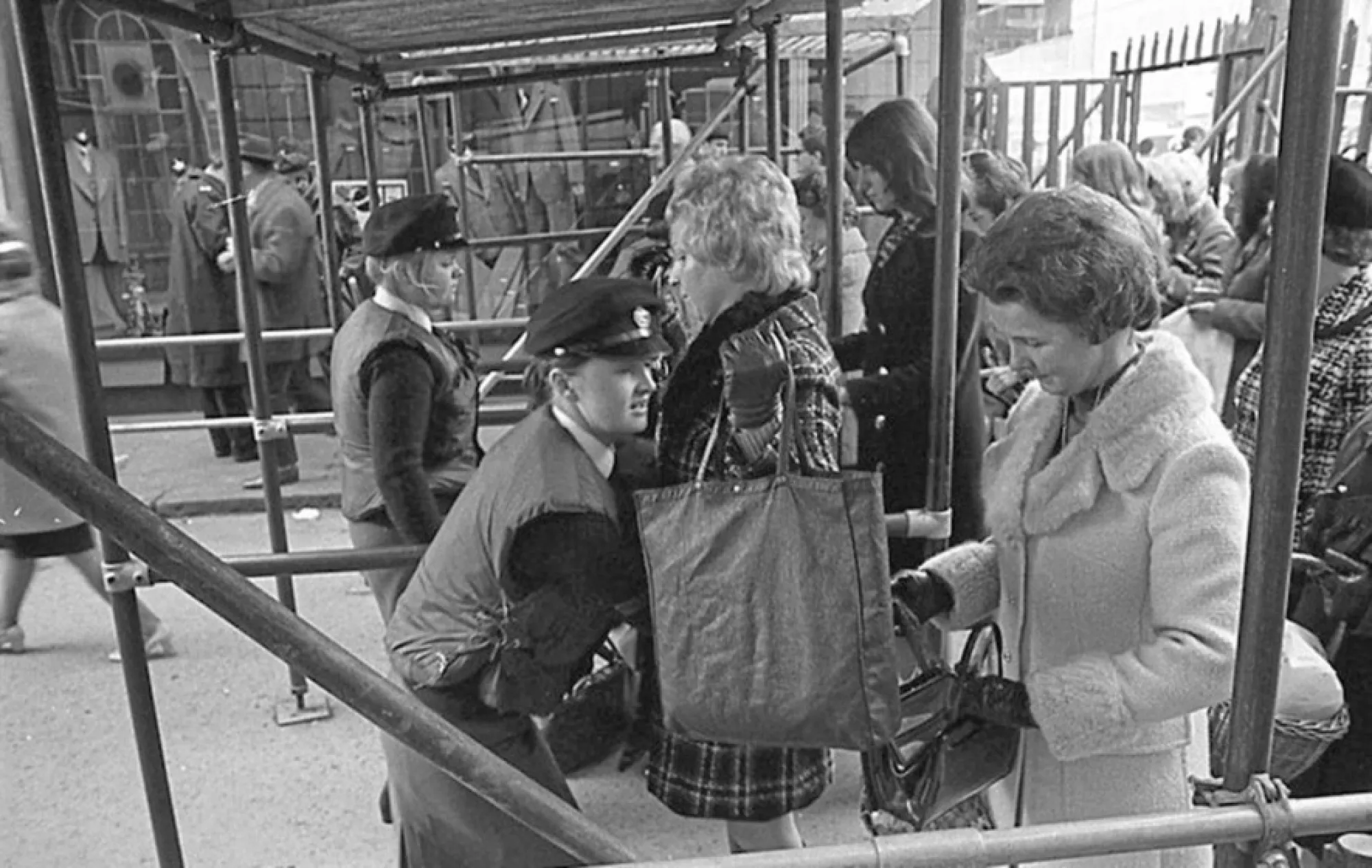

Fifty years ago, the Belfast City Centre was surrounded by barricades, a security cordon meant to keep bombers from entering the city’s commercial center during the Troubles Era, an ethno-nationalist conflict in Northern Ireland. Whether one was rich or poor, Catholic or Protestant, everyone had to pass through the security checkpoint for a pat-down before entering to work, shop or socialize. The cordon, a series of gates, fences, turnstiles, search stations and blocked roads, was known as the Ring of Steel.

The security cordon stayed up for about 20 years, until the 1998 Peace Agreement practically erased all evidence of the Ring of Steel, leaving hardly any trace beyond the memories of those who lived through it. But Belfast residents rarely talked about their experiences, if ever.

“The cordon was hugely political, but nobody said a word about that,” said Kate Catterall, associate professor in the Department of Design.

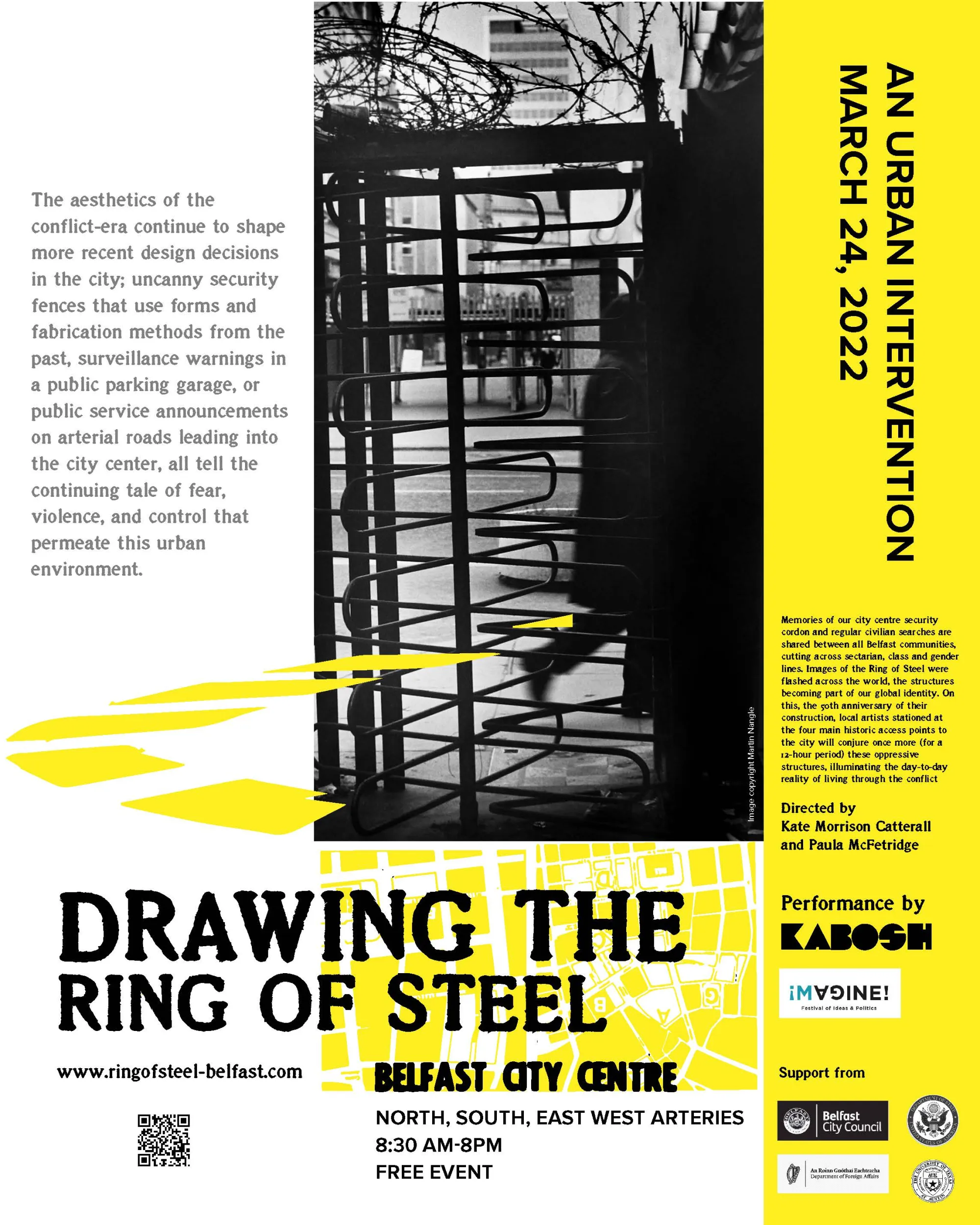

Catterall began working on her project Drawing the Ring of Steel in 2016 while she was teaching in Milan. She wanted to design an experience that would spark a conversation between the older and younger generations, not only about the Ring of Steel, but more broadly about the intense and deadly conflict between the people of Northern Ireland during that time. She wanted to create a reminder of the lives lost and also celebrate those who endured the period and still carry those memories within them. A prototype was installed in chalk and tape opposite Belfast City Hall in 2016 as a proof of concept.

“I stayed there hoping to photograph people coming past it to see if they looked down and recognized what it was because you can tell when people recognize that,” Catterall said. “Well, I got about 40 minutes into it when the police arrived.”

Catterall didn’t have a permit to draw on the ground, and the two police officers were ready to issue her a citation. But then, something clicked in the older officer’s head as he realized that she was recreating a security gate/checkpoint in the old Ring of Steel. The police stayed to talk about the checkpoints and did not ticket Catterall.

Though the younger officer was too young to have experienced the Ring of Steel, Catterall said the encounter sparked a conversation between the two of them about the barricades and what had occurred there, proving Catterall’s point that people could have transgenerational conversations about history. The police officers gave her two hours to work, allowing her to tape down where she remembered the barricades being and photograph the locations.

Born in Belfast, Catterall left Northern Ireland at 18 and has lived in different countries since then. Though she had not lived in Northern Ireland in more than 30 years and knew virtually no one in the city, she began flying there to scope out the location of the old Ring of Steel. She managed to draw up plans of the barricades based on GPS estimates, Google images, period ordnance survey, newspaper photographs and onsite surveys, and she then negotiated with Belfast City Council, the government at Stormont and those who oversee security, roads and transportation to bring the project into being.

In the following years Catterall met with politicians, care workers, community organizers and artists. She ran workshops on shared remembrance of the Troubles at the University of Ulster and arts and community organizations, and she developed working relationships with people who later co-wrote grants with her to finance the project. One of the first people she met with was Lord Alderdice, the speaker of the House in Stormont. Alderdice, a psychiatrist, was able to advise on mitigating the retraumatization of audiences and negotiating the political complexities of the project.

In the end, all those efforts were worth it. Not only did she gain knowledge on how to continue her project, but the concept became ubiquitous, and prior familiarity made meetings for security clearances, permissions and funding more productive and positive.

Catterall met Paula McFetridge, artistic director of Kabosh, a theatre company in Belfast, during a peace conference in 2018; McFetridge was presenting about a controversial play she developed about peacekeeping forces on either side of Northern Ireland/Republic of Ireland border. The pair developed a working relationship, bringing together Catterall’s design research and set and costume design with McFetridge’s experience with performers activating politically charged sites. The project was ultimately funded by the U.S. State Department in London, The Department of Foreign Affairs, Dublin and Belfast City Council.

The project was placed on hold during the COVID-19 pandemic, but the team met on Zoom to develop choreography and keep the project moving forward. One meeting included two police officers who trained civilian search unit personnel during the 1980s. They showed the choreographer how to search, and the choreographer developed movement based on their instructions. They discussed costumes, color schemes and logistics, and it all came together right on time for the 50th anniversary of the Ring of Steel’s construction.

On March 24, 2022, this free 12-hour performative event took place at the four main checkpoints, into and out of the city center, in the former Ring of Steel: Donegall Place, Royal Avenue, Castle Street and High Street. The performers, some wearing period costumes, interviewed passersby to gather memories and stories of the Ring of Steel. Other performers wearing yellow directed pedestrians and enacted search and frisk motions at intervals. Passersby intermingled with performers, inhabiting history, contributing to, or observing, the event.

“It engaged people across the age spectrum, the ability spectrum, the religious spectrum — you name it,” Catterall said. “We met people from every walk of life that day. And there was a real sort of festival feel to it. It was a reminder of back then and a celebration of the fact that the Ring of Steel was gone.”

People came up to Catterall, expressing how their memories of the Troubles had been suppressed, how their kids didn’t want to know about that time but were now asking questions. On the day and for weeks afterward, it seemed that slowly, Belfast residents were opening up to speaking about their past. Local U.K. outlets such BBC Radio, ITV News and The Irish News covered the event, continuing the conversation around the Ring of Steel.

The event lasted only one day, but Catterall is now working on a walking app to lead visitors and locals around the old Ring of Steel, allowing them to see images of the barricades and hear stories from the day of the event as they use the self-guided tour on a smartphone. The prototype is almost ready to share with Belfast’s Department of Culture and Tourism, which is working on a project called Belfast Stories, a collection of archived stories from the area. Drawing the Ring of Steel will be their first exhibition and will serve as a template for future story-gathering projects.

Using design principles, Catterall was able to convince a still-divided city that it was possible to remember a dark time of barricades, bombings and high fatalities, together, illuminating it in a way that sparked a conversation between generations and across sectarian divides.

“It was not a gloomy situation,” she said of the March 24 event. “It was a celebration of having survived.”