Gone (Back) to Texas

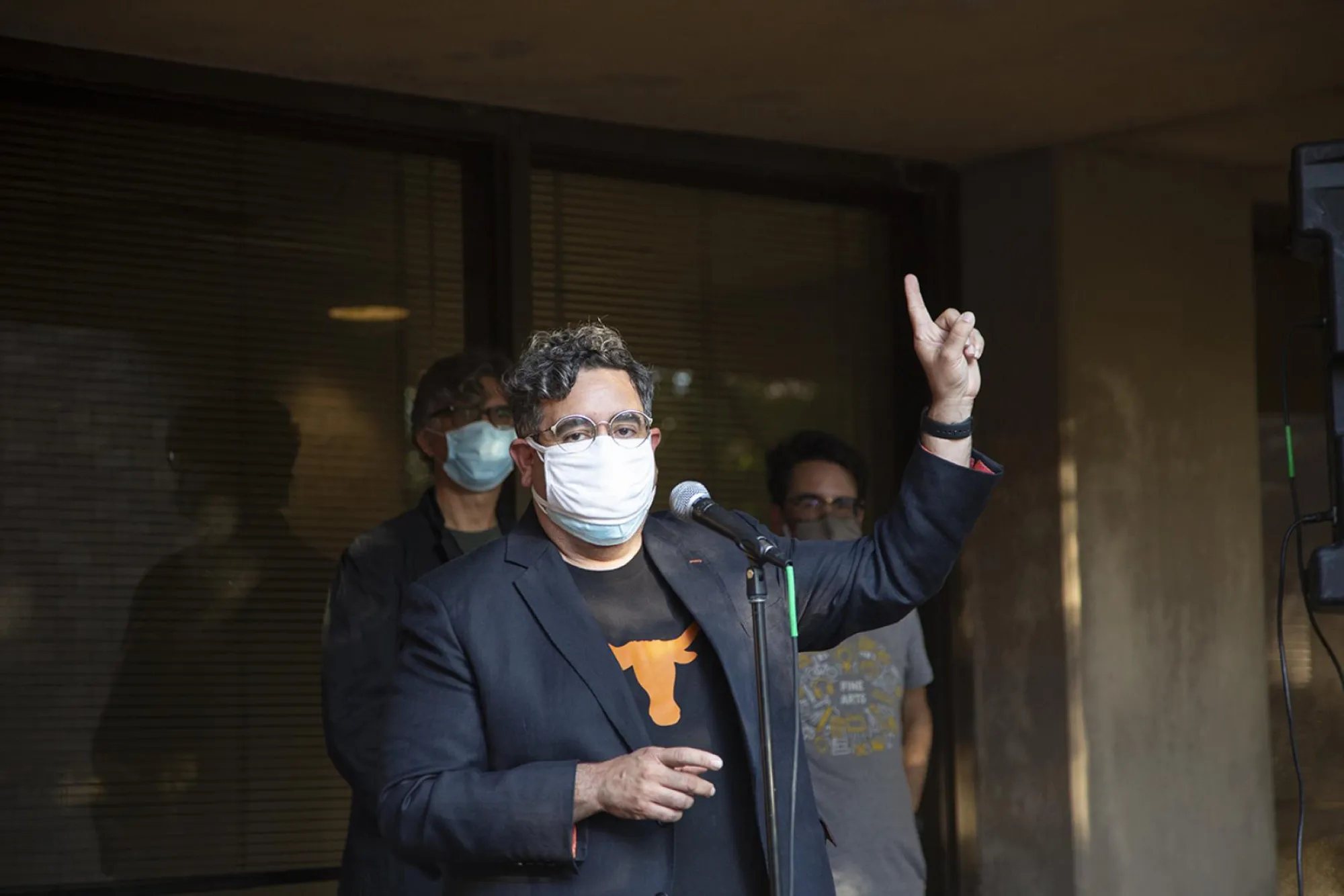

UT alumnus Ramón H. Rivera-Servera draws on deep experiences expanding disciplines and connecting communities as he leads the UT College of Fine Arts

By Alicia Dietrich

Ramón H. Rivera-Servera seems to have a knack for arriving at institutions just as they are on the cusp or in the midst of great transformation. As the UT alumnus takes the reins as dean of the UT College of Fine Arts, he returns to Texas and finds that the college is once again in a period of growth, both in terms of student enrollment and disciplinary expansion in the arts.

Born and raised in San Juan, Puerto Rico, Rivera-Servera grew up competing in science fairs and participating in theater. Although the arts and sciences were always closely intertwined for him, he won the Bausch + Lomb Science Medal alongside a generous fellowship and pursued science as an undergraduate at the University of Rochester. But his scientific studies took a dramatic turn toward the arts after two transformative classes with art historian Douglas Crimp about the emergence of performance art in the art historical canon and the social and cultural history of the AIDS crisis. These courses opened new avenues of inquiry for him, especially around reforming the art historical canon and cultural aesthetics practices around memorializing the AIDS crisis, as the epidemic exposed dramatic disparities in care.

“All of the sudden, a kid that was going to be a science major really turned to aesthetics, to visual culture, to performance as a way of kind of making sense of the world and intervening in the world,” Rivera-Servera said. “So, I declared an art history major immediately, and the rest was history.”

As the field of art history expanded into the study of performance art, the field of theatre history was expanding into new areas of performance studies. Rivera-Servera’s work at the University of Rochester began to gravitate toward theatre and performance studies, with a focus on the performance practices of queer Latinx, African American and other racial and ethnic minorities in the United States. After he completed his studies at Rochester, he moved to New York City to pursue a master’s degree in theatre studies from the City University of New York—a hot spot in the world of performance studies, rich with diverse artists and scholars engaging in these issues.

GONE TO TEXAS

He worked closely with Professor Jill Dolan at CUNY, and in 1999, just as he was completing his first round of doctoral exams, Dolan called Rivera-Servera into her office to share that she was moving to Texas. The Department of Theatre and Dance at The University of Texas at Austin had hired her to come in and revitalize their storied program in theatre history and move it in the direction of performance studies. Would Rivera-Servera like to transfer to Texas and continue his studies there? Drawn by the rich tradition of Latin American Studies scholarship at UT Austin and potential disciplinary crossover, he said yes and packed his bags.

“I arrived at UT Austin at a time when theatre history was expanding its reach and its methodologies,” said Rivera-Servera. “It was bringing practitioners from a wide range of theatrical and performance genres into the scholarly community. I realized that performance studies offered this new direction in the field of theatre history, and at the same time it had a really long history at The University of Texas.” From novelist and playwright Jovita González to Américo Paredes, “Texas had these scholars who had an investment in the practice and had been tending to Latinx, Mexican American communities and Mexican communities in the region.”

Dolan built on the foundation of the Theatre History and Criticism program in the Department of Theatre and Dance to expand it in new directions, and the program was reimagined as Performance as Public Practice. Rivera-Servera was the first doctoral student to graduate from the program.

While he was still a graduate student, Dolan tasked Rivera-Servera with organizing a conference themed around “crossing borders.” The program became the first big conference in Latinx queer performance and brought together performances and scholarship that explored the intersections between research and artistic practice.

“It was just a real laboratory in learning to be a scholar that tended to difficult material in the scholarly philosophical sense, but also thought about sharing it much more widely in translated form and relying on artistic practices as a way of advancing that,” said Rivera-Servera. “It was really a beautiful event that marked the way I conducted my career going forward.”

CONNECTING COMMUNITIES

After leaving UT, Rivera-Servera continued conducting fieldwork, focusing on dance practices among Latinx queer communities in Austin and San Antonio and later in New York’s Bronx. He took jobs at the State University of New York and the University of Rochester, just as the dance program at Rochester was expanding into a larger study of movement and dance.

“The very same skills that I had acquired at UT Austin became incredibly valuable to transforming how students in a dance program thought about movement beyond the dance studio,” said Rivera-Servera. “Now, dance was becoming Dance and Movement Studies, and it was not just looking at artistic genres of dance like ballet and modern dance, but also expanding it to think more critically about how do we move, how do we gesture in everyday contexts.”

His first book, Performing Queer Latinidad: Dance, Sexuality, Politics (University of Michigan Press, 2012), built on his field work, exploring the explosion of Latin American music and dance in mainstream pop culture in the United States in the 1990s and early 2000s—embodied by the rise of Ricky Martin, Jennifer Lopez and Selena—with a particular focus on how the queer Latinx community danced to and engaged with it.

“My book looks at dance as a place where people gathered and imagined themselves as a community in difference, understanding that Latinx communities come from really divergent histories, ethnic nationalities and reasons for arriving in the United States,” Rivera-Servera said. “Within that framework, there’s a whole lot of difference in terms of race, in terms of class, in terms of sexual orientation. Dance, for me, became a catalyst for building community despite all of that difference, in a way that did not surrender the different narratives of each of those communities that gathered at the dance studio or at the dance club or at the cultural center. My work valued the fact that we could dance together despite our difference in techniques or styles and became a real theory of how to think of Latinidad as something that is both about convergences as much as divergences and how those things coexist.”

In his next two roles, Rivera-Servera continued to build communities and catalyze conversations between academia and practitioners in the field. His work pushed the bounds of what historically had been included in conversations in academia and brought in new voices and perspectives to his field.

Arizona State University recruited Rivera-Servera as a Southwest Borderlands scholar in the theatre program in 2003, just as the university was working to expand its faculty with expertise around the American Southwest. In that role, Rivera-Servera developed the Performance in the Borderlands program, a commissioning platform and curatorial program that allowed the university to explore performance practices related to relevant issues in the Southwest, from environmentalism to the lives and prospects of the Hispanic, Indigenous and Black communities in the region.

Northwestern University recruited Rivera-Servera to join their performance studies faculty in 2007. During his 14 years at Northwestern, he began moving into more administrative roles, where he had more influence in new faculty members and students. He was appointed director of graduate studies, and he eventually served as chair of two departments.

“At Northwestern University, I had the opportunity to help shape a new generation of faculty that were coming into the field,” Rivera-Servera said. “By the time I left Northwestern, all but one faculty member arrived there after I did. It’s a beautiful kind of transformation of the field. It’s a primarily BIPOC [Black, Indigenous, People of Color] faculty and a primarily BIPOC student body at the graduate level. It’s a really incredible attestation to where the field has gone in producing new scholarship.”

While at Northwestern, he also launched the Puerto Rican Arts Initiative, a transformative program that supported artists in the wake of hurricanes Irma and Maria in 2017. (See this story for more on the project.) With his new role at UT, the College of Fine Arts will become a new partner in the project and continue building on the work of the past five years.

A RETURN TO TEXAS

When he was approached about applying for the dean position at the UT College of Fine Arts, Rivera-Servera was immediately intrigued. Under the leadership of his predecessor, Dean Doug Dempster, the college had undergone enormous change and transformation in recent years, from expanding what artistic forms are taught to a stronger emphasis on professional career preparation for students inside and outside of the classroom.

“For a thought and practice leader like myself, it's a dream job to come back home and to think about the future of the arts in this expanded and really socially connected way," Rivera-Servera said. "One of the things that I love about the UT College of Fine Arts is that it's not a relic of artwork to be contemplated. We're producing and we're doing the kind of scholarship that is committed to the consequential nature of the arts and the world. To know that the arts are both life-sustaining and at the same time really knowledge-producing in the broadest possible sense. What we do is as much of consequence to people in the arts and humanities as to those in the sciences. Science cannot happen without creativity.”

Rivera-Servera steps into his new role as dean just as the world is emerging from more than a year of pandemic-fueled disruption in higher education and the global arts scene. Rather than feeling daunted, he said he is focused on the opportunities to build on the strengths of the college—its deep sense of community and its breadth and depth of disciplines.

“My curiosity for the arts and my appreciation for what the arts do is not really restricted to one way of doing the arts or one kind of artistic practice,” Rivera-Servera said. As someone who’s spent his entire career migrating and navigating across disciplines, he’s eager to apply his ethnographic research skills to the College of Fine Arts communities to build a shared vision for the college’s future.

“People mistakenly believe the role of leadership as being about coming with a singular vision about the world and translating it to the community that you’re working for,” he said. “Coming from the position of the listener introduces a different ethics about how we see the world and the community that you’re here to serve and lead. I take that really seriously in the sense that I don’t think I have a desire to lead out of a singular vision. My job is really to come in and understand both the difficulties and opportunities within a particular organization. And to understand them as a community that becomes a collective through art as its center, as its core."