Decoding the Codex: Hand-Painted Reproduction of Ancient Aztec Manuscript Offers Fresh Perspectives into Mesoamerican Culture

by Alicia Dietrich / photos by Will Haughey

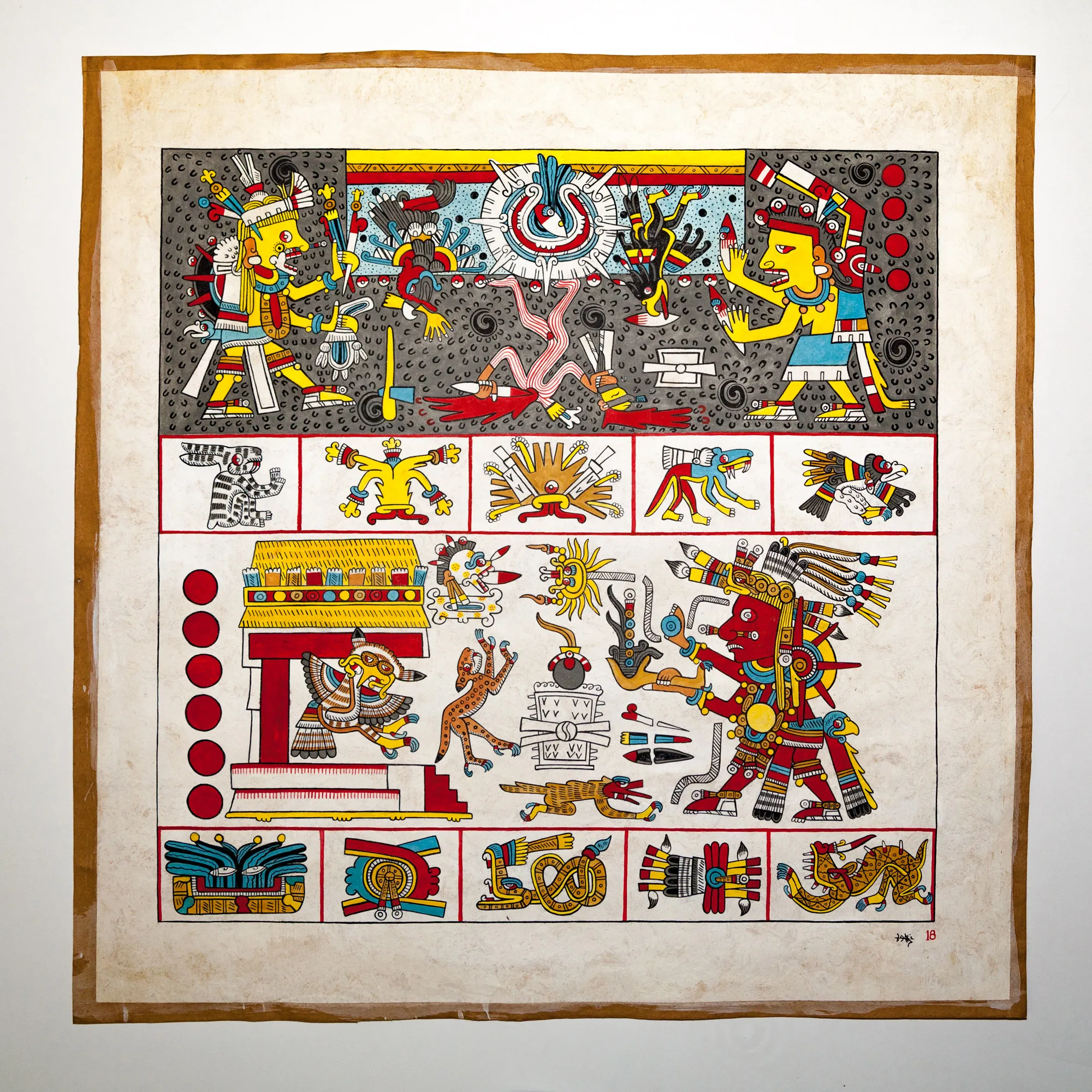

This spring, visitors to the Visual Arts Center had the rare opportunity to see a collection of 76 hand-painted folios that recreate a sixteenth century Aztec manuscript, the Codex Borgia, which survived the burning of books by the Spaniards and lived in obscurity in Vatican archives for centuries.

The folios on display were a work decades in the making, a labor of love by Richard Gutherie, Gisele Díaz and Alan Rodgers. Gutherie—known to his friends as “Ricky Lee”—was the artist who painstakingly hand-painted reproductions of these images on handmade paper from the bark of the amate tree.

Gutherie moved to Mexico in the late 1970s and friends say that he became obsessed with recreating the codex by hand with the original colors and materials. Using color photographs of the original codex in the Vatican for reference, Gutherie created two copies over two decades, often laboring day and night, fueled by cigarettes and Nescafé. Rodgers and Diaz supported Gutherie financially and emotionally during this time and were tireless advocates and champions of the project, working for many years to find a way to bring wider recognition to the project. Gutherie died 16 years ago at age 50, never receiving the recognition he deserved for his life’s work.

“I really believe in my heart that Ricky Lee was brought to this place to do this work, to re-do this book to introduce it back into the world,” said Rodgers. “It was impossible. The whole project was impossible. But as long as he worked on that project, I never had an instant of doubt that the project was going to be completed. Somebody, some spirit wanted that back into this world. Not only is it pretty—it's magical. It's really magical.”

Striking in their bright, saturated colors, the folios are a ritual almanac created in a style sometime between the early 1200s and early 1500s in the area of Tlaxcala and Puebla in the central highlands of Mexico. Diviners and curers would have consulted the codex to identify appropriate ceremonies for each of the 260 days of the ritual calendar, called a tonalpohuali in Nahuatl, the language of the Aztecs. The tonalpohuali would have addressed rituals from when to plant and harvest crops to appropriate offerings for the gods presiding over each day. Very few indigenous works survived destruction by the Spaniards, who believed the ritual subject matter to be proof of practices of idolatry and devil worship. After the fall of the capital of the Aztec empire to Spain in 1521, several indigenous books were sent back to Europe, among other materials and examples of Aztec culture and craft. The Codex Borgia—named after the Borgia family, who owned it at some point—eventually ended up in the Vatican archive, but remained accessible to only a handful of scholars for centuries.

Gutherie’s colorful and faithful reproductions were published by Dover Press in 1993, making the codex readily available to Mesoamerican scholars around the world, but his hand-painted folios have never previously been exhibited.

The folios came to the Visual Arts Center through Rodgers, who approached the Mesoamerica Center to see if they would consider exhibiting them for the first time and give credit to Gutherie as the true artist of the recreations.

“I couldn't sell the art world on this idea because it's not exactly art. It's not exactly history. It's a combination of the two,” said Rodgers.

That combination turned out to be a great fit for the Mesoamerica Center, and the content of the folios dovetailed perfectly with their Mesoamerica Meetings this past January, which focused on “Mesoamerican Philosophies: Animate Matter, Metaphysics and the Natural Environment.”

“We are highlighting the uniquely Mesoamerican idea that there is an inherent life-force in all aspects of the world. What many in Western civilizations may think of as inanimate (such as rocks and mountains and rivers) are alive in the Mesoamerican world, and often have direct relationships with humans,” said Astrid Runggaldier, assistant director of UT’s Mesoamerica Center. “Representations of this animate world abound in the Codex Borgia. The corn plants, for example, have mouths and eyes, while the surface of the earth is represented as a set of gaping jaws. This neatly encapsulates the idea of the earth as a place of emergence, where the boundaries between inanimate and animate are blurred, or rather, do not exist at all.”

Runggaldier reached out to Amy Haupf, interim director of the Visual Arts Center to ask about displaying the objects in the galleries, and as soon as Haupf saw them, she was onboard.

“I think they're just totally fascinating,” said Haupf. “They're funny. They're endlessly compelling, and I hope that people will be sucked into the imagery and lose track of time and make their way around our 75-foot-long table of images.”

Though the Visual Arts Center is known for its focus on contemporary art and highlighting emerging young artists, the project provided a fantastic curatorial opportunity for graduate students in the Department of Art and Art History studying Mesoamerican art. Curatorial fellows from the graduate program created the label text and educational materials for the exhibition, as well as tour materials for all ages coming to visit the galleries. While the wall text was aimed at general audiences without expertise in deciphering pre-Columbian glyphs, a takeaway packet with a more in-depth, academic approach to the images was created for visitors with a more scholarly focus.

“For some reason, Ricky Lee decided this was going to be his life work and that he needed to recreate these paintings,” said Runggaldier. “I think these things probably came alive for him. It somehow spoke to him. And in the process of doing this, he became fixated with it and obsessed with it. But in the process, he did a really great favor to anybody who would want to look at a codex like this.”