Art preparators play critical, collaborative role in bringing an artist’s vision to life in Visual Art Center’s galleries

by Jennifer Irving

Preparators are the invisible hands of the art world. When they’ve done their job well, few or no signs of their presence remain alongside the art. Although art preparators work almost exclusively behind the scenes, their invaluable work largely shapes our museum experiences.

So, what do art preparators do? They install and deinstall exhibitions, pack and unpack the artworks, repair the walls from previous shows, install and set up space-specific lighting and run all audio-visual components of shows. At the Visual Arts Center (VAC), they also fabricate large components made specifically for the gallery space, usually working solely from digital renderings.

At the Visual Arts Center, the core team of preparators is responsible for each exhibition in the galleries throughout the year. Last fall, the VAC hosted its most ambitious exhibition yet, Social Fabric: Art and Activism in Contemporary Brazil. Open from September 2022 to March 2023, the show featured 10 Brazilian artists and spanned installation, painting, performance, photography, sculpture and video.

Most of the artists live and work in Brazil, and preparators had to ensure the execution of their artistic visions and intentions. Oftentimes, artworks do not fit as originally intended within a new space. Working in tandem with the artists, the preparators and curators shape and change different mediums to fit the idiosyncrasies of the VAC’s gallery. Preparators become collaborators with the artists.

For Social Fabric, preparators played a huge part in the fabrication of many of the works, including artist-in-residence Castiel Vitorino Brasileiro’s Jupiter is Here. Celestial is Everything., a site-specific work created for the VAC’s vaulted gallery. Made entirely of natural or reused material, the work began as a constructed wall and piles of stones and soil. Using just a digital rendering, chief preparator Marc Silva and his team gridded out the space, with layouts showing what materials would go in each grid square.

“We spent a few days just shoveling rocks and dirt into wheelbarrows and distributing it around the pattern that we had made on the floor,” said Rachael Starbuck, preparator and gallery coordinator.

One of the most important aspects of Brasileiro’s piece was the lighting. Translating artists’ digital renderings of lighting often presents challenges because of the physical constraints in the gallery space. Starbuck and her colleagues tapped their creativity to find ways to re-create Brasileiro’s plans in the VAC with their existing lighting and equipment.

“It’s crazy to think how much time it took to really adapt it to the space,” said Assistant Curator Maria Emilia Fernandez on Jupiter is Here. Celestial is Everything. “It’s one thing to work on a model or a sketch and another to actually be in the gallery.”

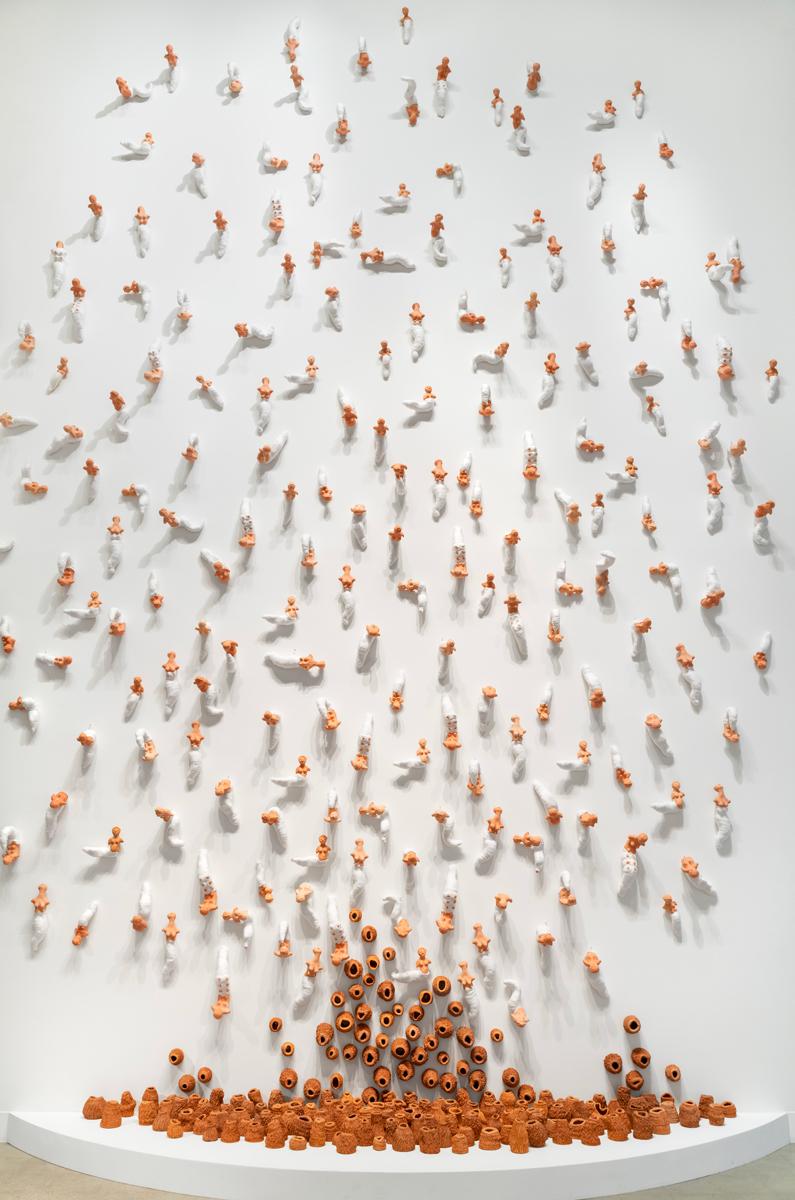

Other works, such as Rosana Paulino’s Tecelãs, involved a similar grid planning process but less actual fabrication. Tecelãs consists of dozens of silkworm weavers and ceramic nests, and the piece is usually placed in a large corner of a gallery. At the VAC, the space is bigger than where it had previously been exhibited and offered a unique opportunity for Paulino to present the work in a new way.

“The artist really wanted us to make sure that it felt like the piece took over the entire wall, to go as high up as we possibly could,” Fernandez said.

Working with the artist, Fernandez mapped out different versions of how to lay out the weavers and the nests, playing with density and placement to create a more tree-like figure. The figures arrived in a variety of shapes and sizes, each with its own specific label. Using Photoshop, Fernandez and Paulino sent diagrams back and forth to each other before deciding on a final layout. For installation, the preparators projected the digital rendering on the wall and placed the objects from the top down.

“If another set of people had hung that piece, I don’t think it would have looked wildly different, but it would definitely have been slightly different,” Starbuck said. “Because of decisions like, ‘Should we put this one next to this one? Should their heads be angled together? Should their tails be angled together? Are they looking squirmy enough? Should they be at right angles?’ We were making a lot of decisions as we were hanging it.”

Fernandez also created the diagram for Sallisa Rosa’s Resistência, a wheatpaste mural made of photos of machetes meant to resemble a wallpaper. For this piece, Rosa asked for the images to be randomly placed, and again Fernandez created and shared diagrams with the artist to see what layout worked best.

Preparators must consider many small details on the wall that could interrupt the work. “Sometimes there’s an emergency light that we must work around,” Fernandez said.

Social Fabric is the most recent show that found the preparators and curators working so closely with the artists for large-scale works, but it is by no means the first or last. Preparators play an enormous role in the final appearance of most shows, even if the public doesn’t notice evidence of their work.

Most preparators are artists themselves, and many hold M.F.A. degrees. Starbuck says an artistic background is one of the most valuable skills a preparator can have. “You have to make so many aesthetic and/or logistical decisions because so much of installing or translating artwork from a drawing or a vision or from one location to another — so much of it is subjective,” she said. “You’re not building like an engineer. There’s not one exact right way to do anything.”

The relationship of trust among artists, curators and preparators is what makes shows in a space like the VAC so very special. Next time you’re in the gallery, pay close attention to all the things you don’t usually see: filled-in holes where previous work hung, wires woven in through the ceiling for different lights, even that flawless fresh coat of paint.

“[The collaboration is] definitely one of the parts of the job that I enjoy the most. It is really trying to listen and understand the artist’s vision,” Fernandez said. “It’s more so like an unspoken rule, or an agreement, that a lot of this legwork to actually adapt a work to a space will be done by the people working there. Because it makes sense, right? We know the galleries better, so it’s up to us to make recommendations.”